ILSOYADVISOR POST

Disease Management: Soil Testing and Liming

Soybean harvest is over and corn harvest is almost complete. It really has been a great fall for harvesting crops – warm and dry. Crops came out rapidly and very little corn needed to be dried, which was quite the savings in time of low commodity prices.

But fall isn’t over because farmers are taking to the fields to do fall tillage and fertilizer application – and of course routine soil testing. Soil testing is important because it helps you track pH, phosphorus and potassium levels in the soil. The value of regular testing is that it provides a trend line of what is happening in the soil, and this data can be used to make a lime and fertilizer recommendation.

In my days as a field agronomist, growers pulled soil samples from bean stubble and then applied fertilizer or lime before the corn crop. Growers usually applied enough lime for a 4-year cycle. It is important to keep the soil pH at 6.2 or above, whether you apply lime before corn or before soybeans.

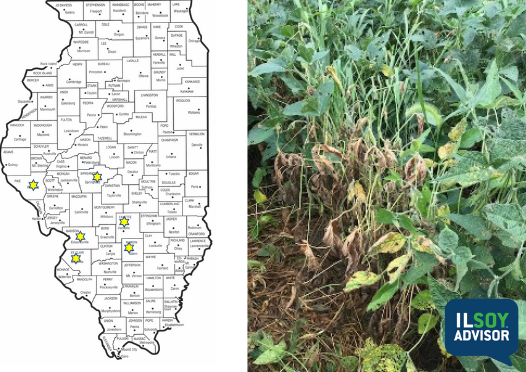

Soybeans are legumes and the rhizobia bacteria are sensitive to pH below 6.2 and EC greater than 1.0 dS/m. Across the Corn Belt we don’t worry about salinity which is measured by electroconductivity (EC), however soil pH tends to be acid, so growers apply lime to raise the pH. For cropping systems with alfalfa, clover, or lespedeza, target a pH of 6.5 or higher. For soybeans target a pH of 6.2. In soils whose pH is neutral below the tillage depth, it is not necessary to apply lime. However, agronomists vary on what is the ideal minimum soil pH for soybeans and that will range from 6.0 to 6.5.

Soil pH also affects nutrient availability and an acid pH solubilizes more aluminum and manganese, which can be toxic to plant roots. Keeping soil pH above 6 optimizes nutrient availability and reduces the risk of metal toxicity.

How much lime to apply? In addition to soil test values, liming rates are determined based on soil type, depth of tillage, limestone quality and crops planted. A legume requires a higher pH than a grain crop for example. A finer textured soil with a higher cation exchange capacity will require more lime to raise pH than a coarser textured sandy soil. The grind and quality of lime also impact application rates.

Lastly, remember that lime (calcium carbonate) dissolves slowly, so apply a finer grind of material in the fall to give it time to dissolve and react with the soil and begin to neutralize soil pH. Also, tillage is of some value to incorporate the lime into the soil through the tillage depth. Liming no-till fields can lead to pH stratification — a high pH for the surface 2 inches, with a lower pH below.

To determine liming rates for Illinois, go to the Illinois Agronomy Handbook published by the University of Illinois. Suggested limestone rates for different soil types are found in in Table 8.3. These rates are based on typical limestone quality and a tillage depth of 8 to 9 inches.

Agronomist Dr. Daniel Davidson posts blogs on agronomy-related topics. Feel free to contact him at djdavidson@agwrite.com or leave a comment below.

Comments

Add new comment