ILSOYADVISOR POST

Early-Season Soybean Management for 2019

This article originally appeared in the University of Illinois the Bulletin.

Average Illinois soybean yield first exceeded 50 bushels per acre in 2004, when it was 50.5 bushels. It was 51.5 bushels in 2010, and 50 bushels in 2013. Over the five years beginning in 2014, it was 56, 56, 59, 58, and, in 2018, an astonishing 65 bushels per acre. Yield in each of the past five years was above trendline, which is a first—the longest stretch of above-trendline yields in the previous 30 years was for three years. In each of the three years 2004, 2014, and 2018, soybean yield exceeded the previous record by about 10 percent. Illinois corn yields were record-high in each of these three years as well, showing that both crops tend to respond similarly to unusually good growing conditions.

Variety selection and maturity

Most people have already selected varieties for 2019. There are a lot of good varieties and a lot of information available on their performance. The University of Illinois soybean variety trials are only a small part of this information, but there are comparisons there that might not be available from other sources. Still, seed companies remain the primary source for information about the varieties they sell, and finding topnotch genetics shouldn’t be too difficult.

One issue that continues to attract interest is how varietal maturity affects yield. In the UI variety trials, entries at each location are separated in roughly equal numbers into two sets: one with longer- and one with shorter-maturity varieties. These sets are planted in separate trials, mostly so the early-maturing ones can be harvested first if a long delay will compromise their performance. Averaged across 5 regions and 13 sites in 2018, the “early” varieties averaged 74.8 bushels per acre, and the “late” ones averaged 73.5 bushels per acre. So across a range of maturities within and among regions running from north (average MG 2.7) to south (average MG 4.2) in Illinois, maturity was not consistently related to yield. We might want to choose a mixture of earlier and later varieties to spread harvest some, but should concentrate more on yield potential than on maturity.

Planting date

We continue to hear a great deal of talk about the need to plant soybeans early in order to get high yields. This is hardly a new discovery: ever since we saw major improvements in seed quality and seed treatments several decades ago, we have known that early-planted soybeans were capable of emerging without the need to wait until soils had warmed up to 55 or 60 degrees before planting.

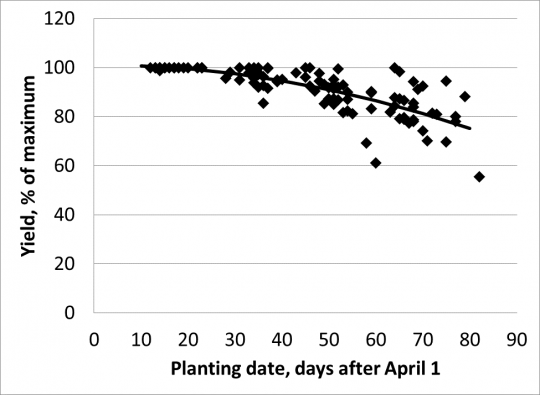

In recent years some have taken “early” planting to an extreme, however, with claims that soybean planting should some before corn planting, as early in March if possible. Figure 1 summarizes the results of 26 planting-date trials conducted in central and northern Illinois between 2010 and 2016. Our target planting dates were in mid-April and then about every two weeks to early June. Planting dates were converted to days after April 1, and yields within each trial to percent of maximum yield for that trial.

Figure 1. Combined results over 26 soybean planting date trials in central and northern Illinois from 2010 through 2016.

We saw little yield decrease when planting was done by May 1 (day 31), about 7% lower yield if planting was on May 15 (day 46), and 14% lower yield if planted on June 1 (day 62). While we did not plant before April 10 in any of these trials, the fact that yields were no higher from planting on April 15 than on April 30 shows that the “early planting” advantage is generally maximized if planting can be done by the end of April.

It’s not clear what advantage there might be in planting soybeans in March, or even, as some did in 2017, in February. Emerged soybean plants are can tolerate low temperatures, with the exception of the few days when the “hypocotyl hook” appears above-ground but before it straightens (in response to light hitting its upper surface) to pull the cotyledons above the soil surface. If frost hits at this point, the exposed hook (stem tissue) can be killed, which kills the seedling. Seedlings are usually in slightly different stages down the row, so frost at this stage will seldom kill all of the seedlings, but it can certainly thin them out.

Soybeans planted in March 2018 encountered cold, wet conditions, including several snow events, during the month after planting. While any emergence under such conditions testifies to the toughness of soybeans, it’s likely that many of these were replanted. Besides stand loss, soybean plants exposed to low temperatures early in the season typically stay short, and often do not yield as much as later-planted soybeans. This shortening might have been partially reversed by increased internode elongation during very warm May weather in 2018. Still, soybeans planted in late April in 2018 also made rapid growth in May and had better stands, so probably yielded more than those that survived March planting. The goal of planting early is not to have the crop survive, but to have it yield more. Low stands and short plants aren’t generally conducive to highest yields, and issues with crop insurance coverage may be another disincentive. There certainly seems to be little reward for taking the risk of planting very early.

Should later-maturing varieties be planted first in order to take maximum advantage of the longer time in the field? There’s no problem with doing that, although early planting moves up harvest date some, so works counter to the goal of spreading harvest time by using different maturities. In 2018 we ran a trial at Urbana, supported by a seed company, to see how varietal maturity affected response to planting date. The first planting date was April 26, the last was June 6, and varieties ranged in maturity from MG 2.3 (very early for this location) to MG 3.6, which is a little later than average for this location.

To read the full article click here.

Comments

Add new comment